Wednesday 23rd June 1971, age 35

My first attempt at Gay Pride.

I’m

at a Gay Liberation Front meeting at All Saints Church Hall in Notting Hill

listening to Micky Burbidge of the counter-psychiatry group describe ‘aversion

therapy’ to several hundred outraged gay people. ‘In this so-called “treatment,”’

he says, ‘gay victims are restrained and stimulated with erotic photos while

electric shocks are administered to their genitals.’ After the cries of shock

and outrage have died down, he asks for volunteers to march down Harley Street

and paint black crosses on the doors of the guilty psychiatrists. I’m one of

the many volunteers who raise their hands.

Two days later, I enter Cavendish

Square to see a tiny group with a banner: ‘NO

TO AVERSION THERAPY’ but am ashamed to admit I don’t dare join them because

they look so few and so vulnerable! I will myself to do it but fail. Nor can I

walk away but instead pathetically follow them along a parallel street

listening to them chanting:

‘Give us a G! … give us an A! …

give us a Y!

What does that spell? – Gay!

What is gay? – Good!

What else is gay? – Angry!’

What does that spell? – Gay!

What is gay? – Good!

What else is gay? – Angry!’

I

silently mouth the replies but still can’t join them which, unfortunately, confirms

another thing Micky said: ‘Self-oppression is the ultimate subjugation which

only succeeds when gay people believe straight

definitions of what is good and bad.’ Chastened but thoughtful, I stumble home

alone.

Next morning I realise

that yesterday was a watershed for me

all the same because acknowledging my

own self-oppression is the first step to overcoming it.

Saturday 28th August 1971, age 35

Taking Pride

The GLF Youth Group have organised a protest march against the male age of consent and this time I’ve eliminated any chance of copping out by wearing my jumpsuit embroidered with ‘Alan’ and ‘Gay Love’ on the epaulets and a rainbow on the breast pocket, plus all my gay badges and a peaked cap also embroidered with ‘Gay Love’ and my name. So I already feel ‘Out and Proud’ as I set off for Marble Arch tube where I find more happy gay people than I’ve seen in my entire life – and also discover that just ‘being in the majority’ is a liberating experience in itself.

Now we’re ambling down Oxford Street past crowds of Saturday shoppers ‘protected’ by the police. It’s true that yesterday I thought people might throw stones at us but today I observe that most simply aren’t interested; a few look scared but many are cheering us on – so, by the time we reach Bond Street I’m so elated I go up to a gorgeous, curly-haired bearded onlooker and say: ‘You’re lovely! Can I kiss you?’

‘Yes, if you want to,’ he says. So I do! Then I do it again with another! And again, for the rest of the day – till I’ve kissed more divine men than I knew existed! I spot two elderly women huffing and puffing at a bus stop, clearly outraged, but today we’re the majority and they’re the psychologically disturbed.

"Fragments of Joy and Sorrow - Memoir of a reluctant revolutionary" by the late Alan Wakeman.

Gemini Press June 2015 - an Imprint of Fantastic Books Company

www.fantasticbooksstore.com © ALAN WAKEMAN 2015

WHAT ARE THE MEMORIES AND THINGS THAT HAVE DEFINED YOUR LGBT+ LIFE?

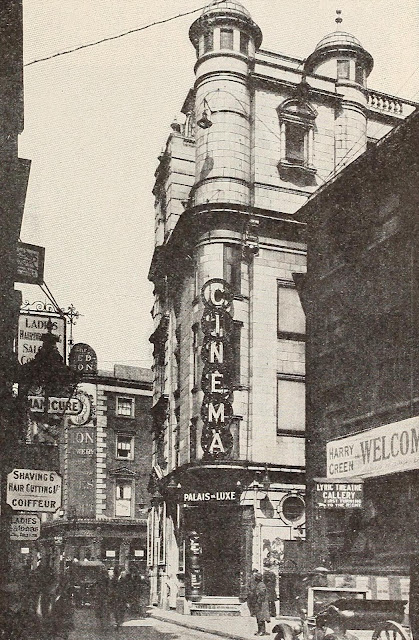

In 2017 the BBC is marking 50 years since the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality. The BBC is crowdsourcing photos, memories, film footage, historic documents, club flyers, outfits, protest banners, posters, music, diary entries and much more to help tell the story of LGBT+ life in Britain from 1967 - 2016. Do you have photos of Soho of yesteryear? Footage of past Prides?

Memorabilia from past Soho clubs, pubs or cabarets? We will be making an interactive crowd sourced archive of LGBT+ life and a BBC television series based around some of the stories, objects and memories contributed. Is there something that has defined your life as an LGBT+ person over the last 50 years? Get in touch and let us know what you have at: history@7wonder.co.uk

Tweet: The BBC is crowdsourcing photos, posters & more to explore #LGBT+ life in Britain 1967-2016. Share what you have: history@7wonder.co.uk

Now we’re ambling down Oxford Street past crowds of Saturday shoppers ‘protected’ by the police. It’s true that yesterday I thought people might throw stones at us but today I observe that most simply aren’t interested; a few look scared but many are cheering us on – so, by the time we reach Bond Street I’m so elated I go up to a gorgeous, curly-haired bearded onlooker and say: ‘You’re lovely! Can I kiss you?’

The Sexual Offences Act 1967 decriminalised ‘homosexual acts

between two men over 21 years of age in private’ in England and Wales only’ excluding the police, the army, the

air force and the navy.

‘Yes, if you want to,’ he says. So I do! Then I do it again with another! And again, for the rest of the day – till I’ve kissed more divine men than I knew existed! I spot two elderly women huffing and puffing at a bus stop, clearly outraged, but today we’re the majority and they’re the psychologically disturbed.

Every now and again I step out to watch my

fellow marchers go by and am struck by what a complete cross-section of

humanity we represent. We could be a crowd from any railway station in the

rush-hour, from ordinary to amazing – especially the dozen drag queens

sashaying at the front – and from my onlooker’s vantage point I carefully note

how many protesters pass each minute and so, once arrived in Trafalgar Square,

am able to calculate that there are about 900 of us altogether.

At

one point I spot a young policeman wistfully shaking his head as he hears us

chanting: ‘Two, four six eight, is that copper really straight?’ and when he

sees me looking he gives me a secret smile.

Next day every national newspaper has

front page photos of our dozen drag queens but not one of our 888 ordinary gay

women and men. Thus stereotypes are maintained and our struggle continues.

Gemini Press June 2015 - an Imprint of Fantastic Books Company

www.fantasticbooksstore.com © ALAN WAKEMAN 2015

WHAT ARE THE MEMORIES AND THINGS THAT HAVE DEFINED YOUR LGBT+ LIFE?

In 2017 the BBC is marking 50 years since the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality. The BBC is crowdsourcing photos, memories, film footage, historic documents, club flyers, outfits, protest banners, posters, music, diary entries and much more to help tell the story of LGBT+ life in Britain from 1967 - 2016. Do you have photos of Soho of yesteryear? Footage of past Prides?

Memorabilia from past Soho clubs, pubs or cabarets? We will be making an interactive crowd sourced archive of LGBT+ life and a BBC television series based around some of the stories, objects and memories contributed. Is there something that has defined your life as an LGBT+ person over the last 50 years? Get in touch and let us know what you have at: history@7wonder.co.uk

Tweet: The BBC is crowdsourcing photos, posters & more to explore #LGBT+ life in Britain 1967-2016. Share what you have: history@7wonder.co.uk